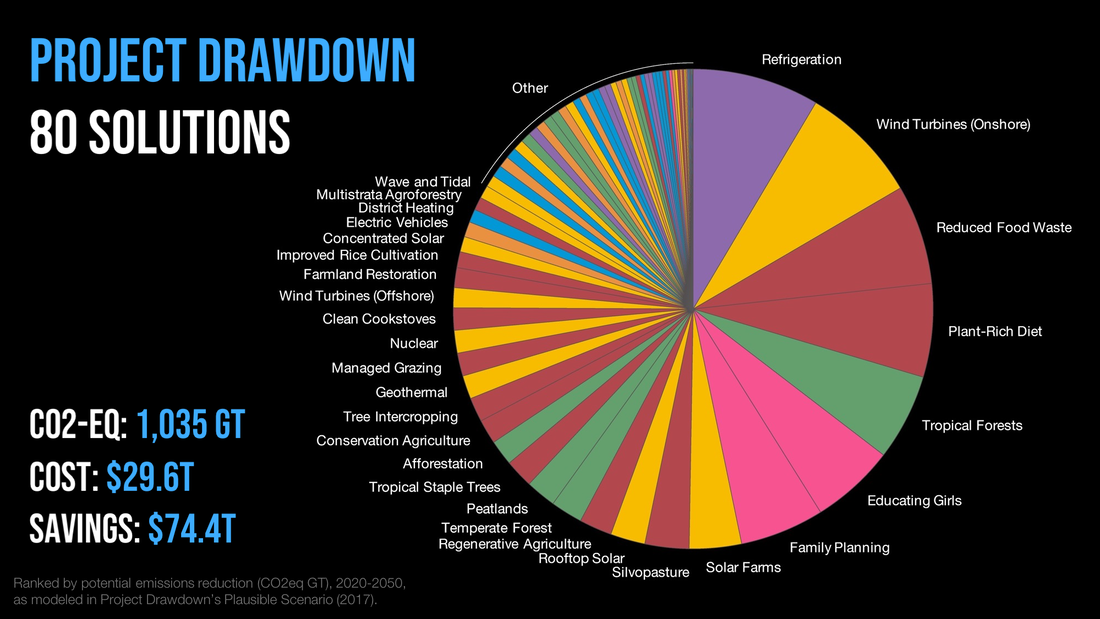

10 Solutions to Stop Global WarmingIn the Project Drawdown analysis, we see an incredible mosaic of solutions, with benefits that go beyond stemming emissions to improving health, creating jobs, and shoring up resilience. We also see roles for every individual and institution on the planet. Climate leadership comes in many forms: Households, cities, companies, social movements and national governments. We need many more pioneers stepping up to lead. It’s a magnificent thing to be alive in a moment that matters as much as this one. Here are 10 solutions that can help us rise to meet the challenge.

INSTALL ROOFTOP SOLAR The first rooftop solar array appeared in 1884 in New York City. At that time, solar panels were made of selenium. They worked, but were inefficient. Today, photovoltaic (PV) panels use thin wafers of silicon crystal. As photons strike them, they knock electrons loose and produce an electrical circuit. These subatomic particles are the only moving parts in a solar panel, which requires no fuel and produces clean electricity. Rooftop solar is spreading as the cost of panels falls, driven by incentives to accelerate growth, economies of scale in manufacturing, and advances in PV technology. Rooftop panels can put electricity generation in the hands of households, communities, and businesses, not just big utilities. They can also leapfrog the need for large-scale, centralized power grids, and accelerate access to affordable, renewable electricity — a powerful means of addressing poverty. Check out: Solar Sister, an organization of women solar entrepreneurs in sub-Saharan Africa. EAT A PLANT-RICH DIET If cattle were their own nation, they would be the world’s third-largest producer of heat-trapping emissions. Why? Because cows belch the potent greenhouse gas methane as they digest their food, and because clearing land for grazing or growing feed is a leading cause of deforestation. Shifting to a diet rich in plants is a powerful climate solution, and one we can act on immediately. It could reduce the emissions created from raising livestock — currently 15 percent or more globally. What’s good for the planet is also good for us. Beyond climate impacts, plant-rich diets also tend to be healthier, leading to lower rates of chronic disease. According to a study from Oxford, business-as-usual food emissions could be reduced by as much as 70 percent through adopting a vegan diet and 63 percent for a vegetarian diet, which includes cheese, milk, and eggs. $1 trillion in annual healthcare costs and lost productivity could be saved. Check out: The Better Buying Lab, which aims to help consumers select more sustainable foods. REDUCE FOOD WASTE A third of the food we produce does not make it from farm to fork. That uneaten food squanders a whole host of resources — seeds, water, energy, land, fertilizer, hours of labor and financial capital. It also generates greenhouse gases at every stage — including methane when organic matter lands in the rubbish bin. The food we waste is responsible for roughly 8 percent of global emissions. In higher-income regions, food is largely wasted by choice. Retailers and consumers reject food based on bumps, bruises, and coloring, or simply order, buy, and serve too much. In places where income is lower and infrastructure is weak, food loss is typically unintended — resulting, for example, from poor storage facilities. Across the board, reducing food waste and loss can improve food security and relieve hunger. Check out: Apeel Sciences’ edible coating, made of plant material, that extends the life of produce. DESIGN SMART HIGHWAYS Look at the average highway and “smart” is probably not the word that comes to mind. Asphalt, traffic, pollution, accidents — highways seem to be the epitome of unsustainable. But efforts are underway to change that, leveraging imagination, technology, and design to reduce emissions and improve safety. Highways have seen very little innovation since their inception. As vehicles go electric and autonomous, can highways evolve and become smart, too? Early answers are emerging on 18 miles of highway southwest of Atlanta, Georgia. A nonprofit, called The Ray, aims to morph this stretch of road into a positive social and environmental force — the world’s first sustainable highway. Electric vehicles can “fuel up” for free at a solar charging station. Lights are powered by a patch of road comprised of PV panels. The Ray is even growing perennial wheat, called Kernza, on the road’s right-of-way, producing food while sequestering carbon. Smart highways are nascent, but look poised to pave the way forward. Check out: Wattway, the world’s first solar photovoltaic road surface. SHIFT TO ELECTRIC VEHICLES There are more than 1 billion cars on the road today, a major source of emissions. Shifting cars from “gas to grid” — that is, to electricity as their fuel — can make mobility dramatically more sustainable and reduce harmful air pollution. Of course, where that electricity comes from matters. All electric vehicles (EVs) have an emissions advantage, but those powered by renewables are the real solution, with 95 percent lower emissions than standard cars. Luckily, that is where electricity generation is headed. While EVs are currently more expensive to purchase, they are cheaper to drive. Their cost will continue to drop in the coming years, as technology improves and production scales. With both charging infra-structure and battery range expanding, EV appeal continues to grow. But cars are not the only electric means of transportation. E-bikes are actually the fastest growing alternative to fuel vehicles in the world. Check out: New Flyer, a company manufacturing electric buses. CREATE WALKABLE CITIES Walkable cities prioritize two feet over four wheels through careful planning and design. They minimize the need to use a car and make the choice to forego driving desirable, which can reduce greenhouse gas emissions. According to the Urban Land Institute, in more compact places ideal for walking, people drive 20 to 40 percent less. Walkable cities can be created from scratch or retrofitted from sprawl, reintegrating spaces for home, work, and play. Walkable trips are not simply those with a manageable distance from point A to point B — perhaps a ten- to fifteen-minute journey on foot. They have “walk appeal,” thanks to a density of fellow pedestrians, a mix of land and real estate uses, and key elements, such as safe crossings and wide, shaded, well-lit sidewalks. All the better if spaces are beautiful. Walkability can improve health, stimulate the local economy, and make urban spaces more usable for all. Check out: Congress for the New Urbanism, a pioneer in walkability and building “places people love.” GROW MORE BAMBOO Humans have found more than 1,000 uses for bamboo, including food, paper, furniture, bicycles, boats, baskets, fabric, charcoal, biofuels, animal feed, and almost every aspect of buildings from frame to floor to shingles. Addressing global warming is another way we can put it to use. Through photosynthesis, bamboo rapidly sequesters carbon, taking it out of the air faster than almost any other plant. Just a grass, bamboo has the compressive strength of concrete and the tensile strength of steel — which means it can be used in place of those high-emissions materials. It reaches its full height in one growing season, at which time it can be harvested for pulp or allowed to grow to maturity over four to eight years. After being cut, bamboo re-sprouts and grows again. What’s more, it can thrive on inhospitable degraded lands, restoring soil and storing carbon. Check out: CUBO, a system of modular bamboo homes designed to address The Philippines’ housing crisis. ENSURE GIRLS' RIGHT TO EDUCATION Securing the rights of women and girls can have a positive impact on the atmosphere, comparable to wind turbines, solar panels, or forests. How so? When girls and women have access to high-quality education, as well as reproductive health care, they have more agency and can make different choices for their lives. Those choices often include marrying later and having fewer children. The decisions individuals make add up. Across the world and over time, they influence how many human beings live on this planet and eat, move, build, produce, consume, and waste — all of which generates emissions. To be sure, those emissions are not generated equally. The affluent produce far more than the poor, and bear greatest responsibility for action. A fundamental right for all, education also shores up resilience and equips girls and women to navigate a climate-changing world. Check out: Room to Read, which is transforming the lives of millions of girls (and boys!) through literacy. ENHANCE HOUSEHOLD RECYCLING The old adage, “reduce, reuse, recycle,” still holds true. Consumption and waste at the individual level contribute to climate change. The best thing to do is stem them upstream — forgoing a purchase or repairing an item. At the very least, the value locked up in “trash” can be reclaimed. Recycling is one means to do that. In high-income countries, paper, plastic, glass, and metal comprise more than 50 percent of the household waste stream — all prime candidates for recycling. Recycling can reduce emissions because producing new products from recovered materials often saves energy. Forging recycled aluminum products, for example, uses 95 percent less energy than creating them from virgin materials. Pair recycling with composting, and what households send to the landfill can shrink considerably. Check out: Recycle Across America’s society-wide, standardized labels for recycling bins, to help people recycle right. BUILD WITH WOOD With the Industrial Revolution, steel and concrete became the main materials for commercial construction. Wood use declined, relegated to single-family homes and low-rise structures. But that is beginning to change with high-performance “mass timber” technologies, namely glued laminated timber (glulam) and cross-laminated timber (CLT). In cities around the world, they are being used to construct tall buildings that are strong, fire safe, quick to put up, and aesthetically appealing. Building with wood has a double climate benefit. First, as trees grow, they absorb and sequester carbon. Dry wood is 50 percent carbon, so a building can become a longstanding carbon sink. Second, the process of producing glulam or CLT generates fewer greenhouse gases than manufacturing cement or steel, each roughly 5 percent of global emissions. To be a true climate solution, wood must be sourced through sustainable forestry, and the less transport the better. Check out: Mjösa Tower, the world’s tallest wooden building, located in Brumunddal, Norway. Myriad Solutions Are Commonly Available, Economically Viable, and Scientifically Valid.With humanity facing the seemingly impossible challenge of climate change, Project Drawdown set out to

discover the world’s most viable solutions. Our team conducted a ground-breaking, global assessment of practices and technologies that are already in hand, or very nearly so. These 100 solutions range from buildings and cities to ecosystems and food, from electricity to materials to transport; they even include human rights. Some stop greenhouse gas emissions from going up, and others bring carbon back home through the power of photosynthesis. Both are critical. There are no “silver bullets,” but there are footholds of action for every individual and every institution on the planet. Taken together, the mosaic of solutions looks a lot like nature in its diversity and brilliance. The Woman Who Discovered the Cause of Global Warming Was Long Overlooked. Her Story Is a Reminder to Champion All Women Leading on Climate.July 17, 2019

Eunice Newton Foote rarely gets the credit she’s due. The American scientist, who was born exactly 200 years ago on Wednesday, was the first woman in climate science. It was back in 1856 that Foote theorized that changes in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere could affect the Earth’s temperature. She broke scientific ground that remains more relevant than ever in 2019, but history overlooked her until just a few years ago. Foote arrived at her breakthrough idea through experimentation. With an air pump, two glass cylinders, and four thermometers, she tested the impact of “carbonic acid gas” (the term for carbon dioxide in her day) against “common air.” When placed in the sun, she found that the cylinder with carbon dioxide trapped more heat and stayed hot longer. From a simple experiment, she drew a profound conclusion: “An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature; and if as some suppose, at one period of its history the air had mixed with it a larger proportion than at present, an increased temperature…must have necessarily resulted.” In other words, she connected the dots between carbon dioxide and global warming. Foote’s paper, “Circumstances Affecting the Heat of Sun’s Rays,” was presented in August 1856 at a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and then published. (For unknown reasons, likely rules or social norms, it was read by a man from The Smithsonian, rather than Foote herself.) That was three years before Irish physicist John Tyndall published his own, more detailed work on heat-trapping gases — work typically credited as the foundation of climate science. Did Tyndall know about Foote’s paper? It’s unclear — though he did have a paper on color blindness in the same 1856 journal as hers. In any case, I have to wonder if Eunice Newton Foote ever found herself remarking, as so many women have: “I literally just said that, dude.” I also find myself wondering: What might Foote have achieved if she had Tyndall’s access to training and resources? We can only imagine. Perhaps we can understand, if not abide, that Foote was hobbled by the conventions and limitations of her day. Perhaps we can also amend that loss by supporting women in climate today. Look around the world, and you will see women and girls making enormous contributions in this space. Conducting research and advancing climate science, to be sure, but also cultivating solutions, creating campaign strategy, curating art exhibits, crafting policy, composing literary work, charging forth in collective action, and more. Look around, and you will see truly catalytic leadership grounded in courage, creativity, compassion, and collaboration. As someone who has worked in climate for two decades, it’s easy for despair to creep in. This groundswell of leadership gives me courage. To my mind, this is where possibility lives — possibility that we can turn away from the brink and move towards a life-giving future for all. Yet, girls and women leading on climate receive insufficient backing and, even now, too little credit. That’s especially true for women of the Global South, rural women, and women of color. Worse than unfair, it’s ineffective for creating change. In the face of the climate crisis, we need every person possible on the task of transforming society. I’m not alone in this belief. Today, a group of women from around the world has released the following declaration: The climate movement cannot succeed without an urgent upsurge in women’s leadership across the Global South and the Global North. Women and girls are already boldly leading on climate justice, addressing the climate crisis in ways that heal, rather than deepen, systemic injustices. Yet, these voices are often under-represented and efforts inadequately supported. Now is the moment to recognize the wisdom and leadership of women and girls. Now is the moment to grow in number and build power. We invite all of our sisters to rise and to lead on climate justice, and for those with relative power and privilege to make space for and support others. To change everything, we need everyone. Signatories to the declaration include Mary Robinson, first female president of Ireland, Musimbi Kanyoro, president and CEO of Global Fund for Women, and Alaa Murabit, medical doctor and one of 17 Global Sustainable Development Goal Advocates appointed by the UN Secretary General. One of the key actions signatories pledged is “to unify women’s efforts to create equity in health, education, economy, politics, peace and security, and beyond with the climate justice movement.” It shows a marked shift towards recognizing that human rights and climate are inseparable. Eunice Newton Foote, if alive today, might be very pleased to find that connection drawn. After all, she wasn’t only a scientist. She was involved in the early movement for women’s rights, too. Her name appears on the list of signatories to the 1848 Seneca Falls Declaration — a manifesto created during the first women’s rights convention in the United States — right below Elizabeth Cady Stanton, of suffragette fame. Foote’s husband, Elisha, and Frederick Douglass also signed on, under “gentlemen.” (Of note: John Tyndall opposed women’s suffrage.) Some 163 years after Foote’s experiment, conditions for women in climate have certainly improved. For one thing, it’s far less lonely than before. But if we want that “urgent upsurge”, it will take commitment, dollars, and platforms. It will demand giving credit where it’s due and continuing to improve inclusion. Now is the time to champion women and girls who lead on climate. And to honor those who came before, whose insight and ability ought not to have been ignored. Cheers to you, Eunice. Women Hold the Key to Curbing Climate ChangeMarch 8, 2019

In 1911, over one million people took to the streets of Austria, Denmark, Germany, and Switzerland for equal rights and suffrage. It was the first International Women’s Day—a day the world continues to celebrate more than a century later. Those inaugural participants had little reason to include heat-trapping emissions or global warming in their concerns, although American scientist Eunice Newton Foote had defined the greenhouse effect decades prior, in 1856. (A first for which more credit is due.) Ice core research shows that Earth’s atmosphere had just over 300 parts per million of carbon dioxide in 1911. In 2019, we hover around 410 parts per million. Those numbers can seem abstract, but they are deeply consequential. At 410 parts per million and rising today, we face a rapidly warming world, with emissions at an all-time high. These are planetary conditions unknown to any human beings before us—and uncharted territory for our survival. Since 1911, we have entered a new geologic age, The Anthropocene, so called because human activity is now the dominant influence shaping the planet. Our warming world is the defining backdrop for International Women’s Day in 2019. The theme of this year’s International Women’s Day—#BalanceforBetter—calls for improved gender parity to improve the world. That aspiration is entangled with climate change in two elemental ways. First, while the negative effects of climate change touch everyone, research shows they hit women and girls hardest. Simultaneously, and surprisingly, advancing key areas of gender equity can help curb the emissions causing the problem. These dual dynamics forge an inextricable link between climate change and the possibility of a more gender-balanced society. Women and girls face disproportionate harm from climate change because it is a powerful “threat multiplier,” making already tenuous situations or existing vulnerabilities worse. We have seen that play out in places from New Orleans after Katrina to Nairobi. Bottom of FormEspecially under conditions of poverty, women and girls face greater risk of displacement or death from natural disasters. Droughts and floods have been tied to early marriage and sexual exploitation—sometimes last-resort survival strategies. Tasks such as collecting water and fuel or growing food fall on female shoulders--sometimes literally—in many cultures. Already challenging and time-consuming activities, climate change can deepen the burden, and with it, struggles for health, education, and financial security. In very real ways, climate change thwarts the rights and opportunities of women and girls. These realities make gender-responsive strategies for climate resilience and adaptation critical. They make centering the rights, voices, and leadership of women and girls a necessity. Turns out, gender is equally important for solutions to stem climate change. Research from Project Drawdown shows that securing the rights of women and girls can have a positive impact on the atmosphere, comparable to wind turbines, solar panels, or forests. Why? In large part because gender equity has ripple effects on growth of our human family. When girls and women have access to high-quality education and reproductive health care, they have more agency and make different choices for their lives. Those choices often include marrying later and having fewer children. The decisions individual women and their partners make add up. Across the world and over time, they influence how many human beings live on this planet and eat, move, build, produce, consume, and waste -- all of which generates emissions. To be sure, those emissions are not generated equally. The affluent produce far more than the poor. The average American produces almost 17 tons of carbon dioxide per capita each year compared to the 1.7 tons or just one-tenth of a ton of someone in India or Madagascar, respectively. Anyone who says curbing population is a silver bullet is ignoring critical variables of production and consumption. We must see the whole ecosystem, not just the trees. Both education and family planning are basic human rights, not yet reality for too many people. Around the world, 130 million school-age girls are not in the classroom. They are missing a vital foundation for life, and that fundamental right must be secured. The same is true for access to high-quality, voluntary reproductive health care. Some 45% of pregnancies in the United States are unintended, while 214 million women in lower-income countries say they want to prevent pregnancy but have “unmet need” for contraception. Policy changes made by the Trump administration are set to worsen both of those statistics, with ripple effects for the planet. Of course, girls’ and women’s leadership on climate also goes way beyond family choices. Many of the vital voices and agents of change for a liveable planet are female. Women and girls are overcoming unequal representation at decision-making tables and underinvestment in their efforts. One need look no further than the example of 16-year-old Swedish activist Greta Thunberg and the growing community of teenage girls leading school strikes for climate around the world. “The climate crisis has already been solved,” Thunberg has said. “We already have all the facts and solutions. All we have to do is to wake up and change. ... So instead of looking for hope, look for action. Then, and only then, hope will come.” I imagine today’s school strikers would find kindred spirits among the participants in International Women’s Day 1911. They are certainly building on the legacy of raising voices and asserting rights. More importantly, they need courageous comrades today. We are reckoning with a planetary challenge of unprecedented scale and severity. The world must mobilize climate solutions as quickly and fully as possible, remembering that gender equity is itself one. Perhaps the silver lining of The Anthropocene is that if human forces can put our planet in the balance, we can also regain equilibrium. It is our choice. That may be the truest, most crucial meaning of #BalanceforBetter. How Gender Equity Can Help Stop Global WarmingNovember 28, 2018

There are two powerful phenomena unfolding on earth: the rise of global warming and the rise of women and girls. The link between them is often overlooked, but gender equity is a key answer to our planetary challenge. Let me explain. For the last few years, I have been working on an effort called “Project Drawdown.” Our team has scoured humanity’s wisdom for solutions to draw down heat-trapping, climate-changing emissions in the atmosphere. Not “someday, maybe, if we’re lucky” solutions. The 80 best practices and technologies already in hand: clean, renewable energy, including solar and wind; green buildings, both new and retrofitted; efficient transportation from Brazil to China; thriving ecosystems through protection and restoration; reducing waste and reclaiming its value; growing food in good ways that regenerate soil; shifting diets to less meat, more plants; and equity for women and girls. Gender and climate are inextricably linked. Drawing down emissions depends on rising up. First, a bit of context. We are in a situation of urgency, severity and scope never before faced by humankind. So far, our response isn’t anywhere close to adequate. But you already know that. You know it in your gut, in your bones. We are each part of the planet’s living systems, knitted together with almost 7.7 billion human beings and 1.8 million known species. We can feel the connections between us. We can feel the brokenness and the closing window to heal it. This earth, our home, is telling us that a better way of being must emerge, and fast. In my experience, to have eyes wide open is to hold a broken heart every day. It’s a grief that I rarely speak, though my work calls on the power of voice. I remind myself that the heart can simply break, or it can break open. A broken-open heart is awake and alive and calls for action. It is regenerative, like nature, reclaiming ruined ground, growing anew. Life moves inexorably toward more life, toward healing, toward wholeness. That’s a fundamental ecological truth. And we, all of us, we are life force. On the face of it, the primary link between women, girls and a warming world is not life but death. Awareness is growing that climate impacts hit women and girls hardest, given existing vulnerabilities. There is greater risk of displacement, higher odds of being injured or killed during a natural disaster. Prolonged drought can precipitate early marriage as families contend with scarcity. Floods can force last-resort prostitution as women struggle to make ends meet. The list goes on and goes wide. These dynamics are most acute under conditions of poverty, from New Orleans to Nairobi. Too often, the story ends here. But not today. Another empowering truth begs to be seen. If we gain ground on gender equity, we also gain ground on addressing global warming. This connection comes to light in three key areas, three areas where we can secure the rights of women and girls, shore up resilience and avert emissions at the same time. Women are the primary farmers of the world. They produce 60 to 80 percent of food in lower-income countries, often operating on fewer than five acres. That’s what the term “smallholder” means. Compared with men, women smallholders have less access to resources, including land rights, credit and capital, training, tools and technology. They farm as capably and efficiently as men, but this well-documented disparity in resources and rights means women produce less food on the same amount of land. Close those gaps, and farm yields rise by 20 to 30 percent. That means 20 to 30 percent more food from the same garden or the same field. The implications for hunger, for health, for household income—they’re obvious. Let’s follow the thread to climate. We humans need land to grow food. Unfortunately, forests are often cleared to supply it, and that causes emissions from deforestation. But if existing farms produce enough food, forests are less likely to be lost. So there’s a ripple effect. Support women smallholders, realize higher yields, avoid deforestation, and sustain the life-giving power of forests. Project Drawdown estimates that addressing inequity in agriculture could prevent two billion tons of emissions between now and 2050. That’s on par with the impact household recycling can have globally. Addressing this inequity can also help women cope with the challenges of growing food as the climate changes. There is life force in cultivation. At last count, 130 million girls are still denied their basic right to attend school. Gaps are greatest in secondary school classrooms. Too many girls are missing a vital foundation for life. Education means better health for women and their children, better financial security, greater agency at home and in society, more capacity to navigate a climate-changing world. Education can mean options, adaptability, strength. It can also mean lower emissions. For a variety of reasons, when we have more years of education, we typically choose to marry later and to have fewer children. So our families end up being smaller. What happens at the individual level adds up, across the world and over time. One by one by one, the right to go to school impacts how many human beings live on this planet and impacts its living systems. That’s not why girls should be educated. It’s one meaningful outcome. Education is one side of a coin. The other is family planning: access to high-quality, voluntary reproductive healthcare. To have children by choice rather than chance is a matter of autonomy and dignity. Yet in the US, 45 percent of pregnancies are unintended. Two hundred and fourteen million women in lower-income countries say they want to decide whether and when to become pregnant but aren’t using contraception. Listening to women’s needs, addressing those needs, advancing equity and well-being: those must be the aims of family planning, period. Curbing the growth of our human population is a side effect, though a potent one. It could dramatically reduce demand for food, transportation, electricity, buildings, goods, and all the rest, thereby reducing emissions. Close the gaps on access to education and family planning, and by mid-century, we may find one billion fewer people inhabiting earth than we would if we do nothing more. According to Project Drawdown, one billion fewer people could mean we avoid more than 100 billion tons of emissions. At that level of impact, gender equity is a top solution to restore a climate fit for life. At that level of impact, gender equity is on par with wind turbines and solar panels and forests. There is life force in learning and life force in choice. Now, let me be clear: this does not mean women and girls are responsible for fixing everything. (Though we probably will.) Equity for women in agriculture, education, and family planning: these are solutions within a system of drawdown solutions. Together, they comprise a blueprint of possibility. And let me be even clearer about this: population cannot be seen in isolation from production or consumption. Some segments of the human family cause exponentially greater harm, while others suffer outsized injustice. The most affluent—we are the most accountable. We have the most to do. The gender-climate connection extends beyond negative impacts and beyond powerful solutions. Women are vital voices and agents for change on this planet, and yet we’re too often missing or even barred from the proverbial table. We’re too often ignored or silenced when we speak. We are too often passed over when plans are laid or investments made. According to one analysis, just 0.2 percent of philanthropic funds go specifically towards women and the environment—merely 110 million dollars globally, the sum spent by one man on a single Basquiat painting last year. These dynamics are not only unjust, they are setting us up for failure. To rapidly, radically reshape society, we need every solution and every solver, every mind, every bit of heart, every set of hands. We often crave a simple call to action, but this challenge demands more than a fact sheet and more than a checklist. We need to function more like an ecosystem, finding strength in our diversity. You know what your superpowers are. You’re an educator, farmer, healer, creator, campaigner, wisdom-keeper. How might you link arms where you are to move solutions forward? There is one role I want to ask that all of you play: the role of messenger. This is a time of great awakening. We need to break the silence around the condition of our planet; move beyond manufactured debates about climate science; share solutions; speak truth with a broken-open heart; teach that to address climate change, we must make gender equity a reality. And in the face of a seemingly impossible challenge, women and girls are a fierce source of possibility. It is a magnificent thing to be alive in a moment that matters so much. This earth, our home, is calling for us to be bold, reminding us we are all in this together—women, men, people of all gender identities, all beings. We are life force. One earth, one chance. Let’s seize it. Project Drawdown’s Blueprint of Possibility to Reverse Global Warming—A Guide for GrantmakingSeptember 5, 2018 Scientists have done an extraordinary job detailing the current and future impacts of global warming. Despite three decades of committed international research, however, no one had developed a comprehensive, actionable, and convincing path forward to reverse it. Humanity has been more adept at imagining the end of civilization than its transformation, and more inclined to throw up our hands in despair or to dream of silver-bullet saviors, however unlikely. Detachment and disengagement has been the norm. Many powerful solutions have gone unnoticed or are unknown.

Our work is proving to be a critical resource for funders to frame solutions and guide grantmaking, both in the U.S. and internationally. The $1 million Roddenberry Prize took inspiration from Drawdown, focusing on food waste, plant-rich diets, girls’ education, and women’s rights—solutions the Roddenberry Foundation identified as generally underfunded and often unrecognized for their impact on climate change. “It’s all in the data,” they put it simply. “At the Foundation, we’re moving away from silver-bullet approaches that emphasize innovation and future technologies at the expense of what we know already works. When we learned about Project Drawdown, we found an opportunity to highlight projects that are already working and support them to scale; seek out creative approaches from diverse members of our global community; and catalyze a shift from a fractured and siloed approach to climate change, to one where the community supports and recognizes its own.” The Skoll Foundation also honed in on our work at the intersection of climate solutions and gender equity. We used Drawdown to frame exploration of a key topic at this year’s Skoll World Forum: women and girls’ central role in “Catalyzing Change in the Climate Crisis.” All too often, the gender-climate nexus is absent in discussions of global warming—particularly solutions to it. Drawdown lifts up and quantifies the importance of securing access to high-quality, voluntary family planning and of addressing gender gaps in educationand smallholder farming. All three must be advanced for the benefit of women, girls, their families and communities. Doing so will also have positive ripple effects on emissions, as well as resilience. Katharine Wilkinson frames and moderates an impassioned conversation with Wanjira Mathai of wPOWER, Agnes Leina of Il’laramatak Community Concerns, and Willy Foote of Root Capital at the 2018 Skoll World Forum. The Ray C. Anderson Foundation has been the longest standing contributor to Project Drawdown, and one of the most substantial. “More than a resource for us, we see Drawdown as our partner in a shared theory of change,” Executive Director John Lanier explains. “We have to prove the possible to create it. That’s exactly what Ray Anderson did as founder, CEO, and chairman of Interface—rather than pointing to problems and spreading fear, he showed what was possible. Ray knew that’s what moves people to action, and Project Drawdown is doing it for the greatest challenge facing humanity.” That approach seems to be working. Organizations and initiatives focused on Drawdown are emerging and taking root worldwide. They are led by educators, NGOs, collaboratives, investors, businesses, artists, and engaged citizens. For news on these evolving efforts, grantmakers can subscribe to Project Drawdown updates at www.drawdown.org and follow @ProjectDrawdown. Within Project Drawdown itself, the research team is updating our global systems model with new data and additional solutions and sectors. Research Fellows from diverse fields and six continents initially shaped this work; more are joining the community, bringing different perspectives. University and other research partners are joining together to regionalize the global model, in order to make it pertinent and useful to cities, states, provinces, and countries. Through communication, Project Drawdown continues to elevate the climate conversation. Dominant messages of threat-and-fear and us-versus-them, intended to spark action, can yield inertia if not indifference. Discourses on climate change filled with jargon may confuse, exclude, and disempower. Better communication is a prerequisite for needed action. Our goal is to craft accessible, actionable content, marked by good storytelling and design—communication that fundamentally transforms the way people understand global warming. Drawdown is and will be disseminated through digital platforms, numerous translations, a TV series, educational curricula, media, and speaking appearances. Drawdown illustrates that there is no shortage of solutions. The technologies and practices we model and share with the world have extraordinary benefits for all people and places. They offer footholds of action for every individual and institution. Greater awareness of solutions creates greater action and participation. Through the work of Project Drawdown, people are seeing possibility come into focus, then committing to make it reality. Drawdown and the Sustainable Development Goals Drawdown Celebrates One Year Since Publication; |

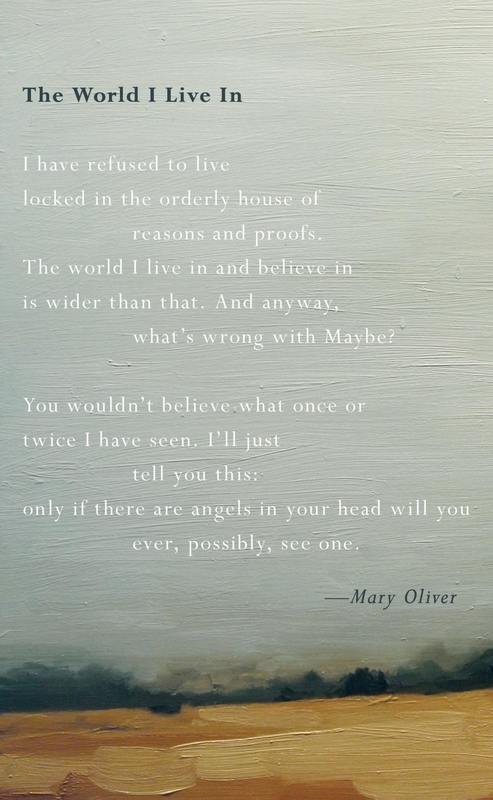

| Of late, I find myself concluding most talks with the wise, supple words of the American poet Mary Oliver, whose work I first came to love at age 16. So very many of her poems are relevant and resonant—“Mindful,” “Messenger,” “The Summer Day,” and “Wild Geese” all come to mind. But the poem that most potently expresses the sentiments I want to share, and from which I take the most sustenance, is “The World I Live In,” found in Oliver’s recent collection Felicity. I have refused to live locked in the orderly house of reasons and proofs, she writes. And why is that, Ms. Oliver? The world I live in and believe in is wider than that. And anyway, what’s wrong with Maybe? Capitalized, she lifts “Maybe” to our attention, making it more official and consequential than a common, lowercase word. (Yes, what is wrong with Maybe? We may find ourselves asking.) You wouldn’t believe what once or twice I have seen, she continues, conveying the wonder that is her hallmark as a poet. And then she seems to let us in on her truest secret. I’ll just tell you this: only if there are angels in your head will you ever, possibly, see one. “Maybe” becomes much more—an angel in our heads, a vision that has faint but magnificent contours. | Image Credit: Penguin Random House |

Many see in Drawdown a catalogue of technologies and practices that, deployed together, can reach “drawdown”—that point in time when the quantity of greenhouse gases in our atmosphere peaks and then declines year over year. Drawdown certainly is that: 100 means to avoid the release of emissions and to bring carbon back home. But by collecting those solutions in a single mosaic, it is also much more. The book begins to envision the world we might create in the process of reversing global warming. The solutions to reach drawdown are also means of building a more vibrant, equitable, and beautiful world—a world of greater health, wellbeing, and happiness.

The most important solution to reverse global warming, I believe, is one that isn’t explicitly catalogued in Drawdown. It is our human capacity to have and continually renew a vision of possibility. For me, real vulnerability and courage are involved in holding space for “Maybe” against long odds, yet that is what I do every time I speak about Drawdown. The great teacher and thinker Parker Palmer calls this “the work before the work,” or the work to stay in the work, of social transformation. It’s deeply necessary and deeply human work. Humans, after all—our heads, hearts, and hands—will be the ones to move the drawdown solutions forward. May we support one another, as we take threads of possibility, one by one by one, and weave the reality of our future, together.

The most important solution to reverse global warming, I believe, is one that isn’t explicitly catalogued in Drawdown. It is our human capacity to have and continually renew a vision of possibility. For me, real vulnerability and courage are involved in holding space for “Maybe” against long odds, yet that is what I do every time I speak about Drawdown. The great teacher and thinker Parker Palmer calls this “the work before the work,” or the work to stay in the work, of social transformation. It’s deeply necessary and deeply human work. Humans, after all—our heads, hearts, and hands—will be the ones to move the drawdown solutions forward. May we support one another, as we take threads of possibility, one by one by one, and weave the reality of our future, together.

Seven Audacious Ideas to Reverse Global Warming

June 14, 2017

"How do we solve a problem like climate change? In the new book Drawdown, a team of over 200 scholars, scientists, policymakers, business leaders, and activists propose 100 practical solutions. Here, the project's senior writer Katharine Wilkinson reveals seven of the most audacious and surprising ideas proposed so far."

Living Buildings

Living buildingsHow do you make a building that improves the world? That’s the central question behind the Living Building Challenge (LBC), first issued in 2006 and now a program run by the International Living Future Institute.

LBC’s holistic approach has seven categories—Place, Water, Energy, Health and Happiness, Materials, Equity, and Beauty—that together define what a living building is and does. Living buildings should grow food and use rainwater, for example, while integrating elements of the natural environment ('biophilic design') and eschewing toxic, 'red-listed' materials.

When it comes to greenhouse gas emissions, living buildings make their greatest impact by producing more energy than they consume. More than 350 buildings are in various stages of LBC certification, showing us that our constructions can do more than simply be less bad: they can generate a net surplus of positives for people and planet.

Artificial Leaf

Imagine an energy source accessible and affordable to all—and available almost anywhere on the planet. That is the aim of the artificial leaf project, founded by Daniel Nocera, a Harvard professor of energy science. The inspiration is obvious: leaves are masterful at harvesting the energy of the Sun through photosynthesis, converting it into energy-rich biomass and sequestering carbon in the process.

Last year, Nocera and fellow professor Pamela Silver announced a giant step towards the goal of inexpensive fuel made with sunshine, water, air...and bacteria. First, a solar-powered process breaks water (H2O) into hydrogen and oxygen. Then, engineered bacteria consume the hydrogen, along with carbon dioxide, and synthesise alcohol fuel. With higher efficiency than natural photosynthesis, the artificial leaf may someday become a real source of energy.

Direct Air Capture

Like the artificial leaf, direct air capture (DAC) takes its inspiration from photosynthesis—the capture and transformation of carbon dioxide into plant matter. DAC machines act like a two-in-one chemical sieve and sponge. As the air passes over a solid or liquid substance, the carbon dioxide binds with chemicals that are selectively 'sticky', ineffective on other gases. Once those capture chemicals become fully saturated, molecules of carbon dioxide can be extracted in purified form.

DAC shows promise for sequestering the planet’s most abundant greenhouse gas. What’s more, captured carbon dioxide can find a wide range of uses—from enhancement for greenhouses to synthetic transportation fuels to plastic, cement, and carbon fibre—though most are still nascent technologies. If DAC developers prove the technology can be both energy-efficient and cost-effective, its future will be bright.

Smart Highways

On 29 kilometres of highway located south of Atlanta, Georgia, an initiative called The Ray is working to morph a stretch of asphalt into a positive social and environmental force: the world’s first sustainable, 'smart' highway.

Electric vehicles and clean energy are focal points for The Ray: infrastructure for solar-powered car charging, a solar photovoltaic (PV) farm along the highway right-of-way, and even PV road surfaces. The aptly named Wattway, a French technology, is a road surface that will produce solar electricity while improving tyre grip and surface durability.

Modern motorways have seen little advancement in design since their inception. Given climate change and the arrival of electric and autonomous vehicles, they need a smarter way forward. The Ray and other pioneers may prove that this dated infrastructure can become clean, safe, and even elegant.

Hyperloop

Can we move transport beyond planes, trains, and automobiles? Inventor and entrepreneur Elon Musk imagines that humans and freight will, before long, have the option to travel through low-pressure tubes by levitated pod. He calls that vision the Hyperloop.

The promise of the Hyperloop is two-fold: speed—up to 1200 kilometres per hour—and efficiency—trimming energy use by 90 to 95 per cent. Both are aided by eliminating the friction of wheels and resistance of air.

Musk has made the Hyperloop concept public, tapping competition as an accelerant for its development. To date, various entities have built prototypes, and successful test runs are now on the books. Ultimately, passengers could glide from Amsterdam to Paris or San Francisco to Los Angeles in roughly half an hour—for the cost of a bus ticket.

Microbial Farming

Plants need nitrogen to grow. Today, many farmers supplement their fields with synthetic nitrogen fertilisers. While crop yields may rise, producing such fertilisers is energy-intensive. Unused nitrogen also migrates into waterways, causing overgrowth of algae and marine 'dead zones', and into the air as the potent greenhouse gas nitrous oxide.

Enhancing the soil microbiome—the microbes that call the soil home—offers a better way of nourishing plants. In a thimble’s worth of soil, there can be up to 10 billion microbial denizens: bacteria, nematodes, fungi, and more. Legumes, such as alfalfa and peanuts, have a symbiotic relationship with select bacteria, passing carbon to them in exchange for nitrogen.

Most crops lack this ability, which is why scientists are looking to harness microbes that can work more broadly—with wheat, rice, and more. Someday, farmers may opt out of nitrogen fertilisers and use nitrogen-fixing bacteria instead.

Repopulating the Mammoth Steppe

Permafrost is a thick layer of perennially frozen, carbon-rich soil that covers a quarter of the Northern Hemisphere. Perma indicates permanence, but this soil is thawing as the world warms, releasing greenhouse gases in the process. Sergey and Nikita Zimov, father-and-son scientists, are piloting a solution in Siberia: returning native fauna to the area.

A grassland ecosystem called the mammoth steppe once spanned the regions where permafrost is found. Today, herbivores no longer roam the region, except at the Zimovs’ Pleistocene Park. When Yakutian horses, reindeer, musk oxen and the like push away snow and expose the turf underneath, the soil is no longer insulated and drops a couple of degrees in temperature—just enough to remain frozen.

Repopulating the mammoth steppe more broadly, the Zimovs say, could help to keep the permafrost frozen, and the greenhouse gases locked up.

link to article

"How do we solve a problem like climate change? In the new book Drawdown, a team of over 200 scholars, scientists, policymakers, business leaders, and activists propose 100 practical solutions. Here, the project's senior writer Katharine Wilkinson reveals seven of the most audacious and surprising ideas proposed so far."

Living Buildings

Living buildingsHow do you make a building that improves the world? That’s the central question behind the Living Building Challenge (LBC), first issued in 2006 and now a program run by the International Living Future Institute.

LBC’s holistic approach has seven categories—Place, Water, Energy, Health and Happiness, Materials, Equity, and Beauty—that together define what a living building is and does. Living buildings should grow food and use rainwater, for example, while integrating elements of the natural environment ('biophilic design') and eschewing toxic, 'red-listed' materials.

When it comes to greenhouse gas emissions, living buildings make their greatest impact by producing more energy than they consume. More than 350 buildings are in various stages of LBC certification, showing us that our constructions can do more than simply be less bad: they can generate a net surplus of positives for people and planet.

Artificial Leaf

Imagine an energy source accessible and affordable to all—and available almost anywhere on the planet. That is the aim of the artificial leaf project, founded by Daniel Nocera, a Harvard professor of energy science. The inspiration is obvious: leaves are masterful at harvesting the energy of the Sun through photosynthesis, converting it into energy-rich biomass and sequestering carbon in the process.

Last year, Nocera and fellow professor Pamela Silver announced a giant step towards the goal of inexpensive fuel made with sunshine, water, air...and bacteria. First, a solar-powered process breaks water (H2O) into hydrogen and oxygen. Then, engineered bacteria consume the hydrogen, along with carbon dioxide, and synthesise alcohol fuel. With higher efficiency than natural photosynthesis, the artificial leaf may someday become a real source of energy.

Direct Air Capture

Like the artificial leaf, direct air capture (DAC) takes its inspiration from photosynthesis—the capture and transformation of carbon dioxide into plant matter. DAC machines act like a two-in-one chemical sieve and sponge. As the air passes over a solid or liquid substance, the carbon dioxide binds with chemicals that are selectively 'sticky', ineffective on other gases. Once those capture chemicals become fully saturated, molecules of carbon dioxide can be extracted in purified form.

DAC shows promise for sequestering the planet’s most abundant greenhouse gas. What’s more, captured carbon dioxide can find a wide range of uses—from enhancement for greenhouses to synthetic transportation fuels to plastic, cement, and carbon fibre—though most are still nascent technologies. If DAC developers prove the technology can be both energy-efficient and cost-effective, its future will be bright.

Smart Highways

On 29 kilometres of highway located south of Atlanta, Georgia, an initiative called The Ray is working to morph a stretch of asphalt into a positive social and environmental force: the world’s first sustainable, 'smart' highway.

Electric vehicles and clean energy are focal points for The Ray: infrastructure for solar-powered car charging, a solar photovoltaic (PV) farm along the highway right-of-way, and even PV road surfaces. The aptly named Wattway, a French technology, is a road surface that will produce solar electricity while improving tyre grip and surface durability.

Modern motorways have seen little advancement in design since their inception. Given climate change and the arrival of electric and autonomous vehicles, they need a smarter way forward. The Ray and other pioneers may prove that this dated infrastructure can become clean, safe, and even elegant.

Hyperloop

Can we move transport beyond planes, trains, and automobiles? Inventor and entrepreneur Elon Musk imagines that humans and freight will, before long, have the option to travel through low-pressure tubes by levitated pod. He calls that vision the Hyperloop.

The promise of the Hyperloop is two-fold: speed—up to 1200 kilometres per hour—and efficiency—trimming energy use by 90 to 95 per cent. Both are aided by eliminating the friction of wheels and resistance of air.

Musk has made the Hyperloop concept public, tapping competition as an accelerant for its development. To date, various entities have built prototypes, and successful test runs are now on the books. Ultimately, passengers could glide from Amsterdam to Paris or San Francisco to Los Angeles in roughly half an hour—for the cost of a bus ticket.

Microbial Farming

Plants need nitrogen to grow. Today, many farmers supplement their fields with synthetic nitrogen fertilisers. While crop yields may rise, producing such fertilisers is energy-intensive. Unused nitrogen also migrates into waterways, causing overgrowth of algae and marine 'dead zones', and into the air as the potent greenhouse gas nitrous oxide.

Enhancing the soil microbiome—the microbes that call the soil home—offers a better way of nourishing plants. In a thimble’s worth of soil, there can be up to 10 billion microbial denizens: bacteria, nematodes, fungi, and more. Legumes, such as alfalfa and peanuts, have a symbiotic relationship with select bacteria, passing carbon to them in exchange for nitrogen.

Most crops lack this ability, which is why scientists are looking to harness microbes that can work more broadly—with wheat, rice, and more. Someday, farmers may opt out of nitrogen fertilisers and use nitrogen-fixing bacteria instead.

Repopulating the Mammoth Steppe

Permafrost is a thick layer of perennially frozen, carbon-rich soil that covers a quarter of the Northern Hemisphere. Perma indicates permanence, but this soil is thawing as the world warms, releasing greenhouse gases in the process. Sergey and Nikita Zimov, father-and-son scientists, are piloting a solution in Siberia: returning native fauna to the area.

A grassland ecosystem called the mammoth steppe once spanned the regions where permafrost is found. Today, herbivores no longer roam the region, except at the Zimovs’ Pleistocene Park. When Yakutian horses, reindeer, musk oxen and the like push away snow and expose the turf underneath, the soil is no longer insulated and drops a couple of degrees in temperature—just enough to remain frozen.

Repopulating the mammoth steppe more broadly, the Zimovs say, could help to keep the permafrost frozen, and the greenhouse gases locked up.

link to article

Beyond the Tyranny of Should

Co-authored with Jen Robinson

December 2015

In 1977, twenty-four women arrived in Oxford as the first female Rhodes Scholars. In the spring of 2008, we celebrated the 30th anniversary of that event with a global, cross-generational gathering of Scholars at Rhodes House. For many of us in residence at the time, the highlight was a talk by Karen Stevenson (Maryland/DC & Magdalen 1979). In a space so often marked by efforts to impress, posture, upstage, Karen shared her own story with authenticity and vulnerability. She spoke openly about the taboo topic of coming unhinged at Oxford – and about finding a critical community of support amongst Rhodes women.

Over seven years later, many details of her talk have become hazy. But the feeling in the Beit Room that day remains palpable, as does Karen’s crystallization of an experience we, as Scholars, were watching unfold around us, if not encountering ourselves: “unhinging.” Unhinging is decidedly not included in scholarly criteria laid out in Cecil Rhodes’ will. It is decidedly not depicted in portraits adorning the walls of Milner Hall, nor is it catalogued in class letters. And how in the world can anyone coming unhinged “fight the world’s fight”? Yet, for many Scholars, it’s a defining element of the Rhodes experience and, as we have learned since, one of the most critical elements in discovering how we might each fight a good fight in our own way.

What is that unhinging all about? We can only speak with confidence about the stories we know well: our own and those of our close community of Rhodes women, specifically Jeni Whalan (Australia-at-Large & Balliol 2005) and Alex Conliffe (Quebec & Hertford 2004). So that’s our dataset, and we’ll use it to tease out the insights we’ve uncovered through explorations in and with that community – insights that are, necessarily, still emerging and far from definitive.

Let’s be honest, most Rhodes Scholars are really, truly excellent box-tickers. Throughout adolescence and as undergraduates, we diligently, passionately, meet and exceed the expectations of our elders and institutions – wowing teachers of all subjects, setting high water marks for our coaches and instructors, impressing anyone excited by excellence, amassing accolades and awards. Indeed, identifying and excelling at ticking boxes of “success” paves the way to the Rhodes.

We arrive at Oxford, then, having perfected the art of should, and often keenly attuned to the shoulds that can feel bound up with the Scholarship itself: to live up to the potential perceived in us, to pursue a path that befits a Rhodes Scholar, to “fight the world’s fight” in some terribly (and conventionally) impressive way. McKinsey. Google. Yale Law. Prestigious government jobs. Even as Scholars are transitioning to Oxford, they’re already wrestling with the transition beyond the dreaming spires. And deploying should against one another, assessing one another’s notions and choices, can become all too regular a pastime.

As Katharine described in The American Oxonian during our second year: “As we squeeze out of Oxford rich and wonderful experiences, we are haunted by anxiety about what comes afterwards. […] For a group of people who, in many ways, have gotten where they are by seeking to please and have received the constant confirmation that comes along with being a pleaser, the real challenge is being our own evaluators and finding our own sources of satisfaction.” It is no small task to discern a sense of direction and purpose in what Mary Oliver has called our one wild and precious life, and that challenge is only intensified when should looms so large. Too often it blurs our vision, rather than sharpening it, and hems us in, rather than fostering exploration of richer paths.

For our band of Rhodes women, our wrestling with Oxford-and-beyond came in waves – as did the unhinging that accompanied it. For Katharine, it started with transitioning out of an ill-suited MSc and into a deeply enriching DPhil, despite American academic mentors urging that she pursue a “real PhD” in the U.S. Jen, on the other hand, recalls that it started during the DPhil:

December 2015

In 1977, twenty-four women arrived in Oxford as the first female Rhodes Scholars. In the spring of 2008, we celebrated the 30th anniversary of that event with a global, cross-generational gathering of Scholars at Rhodes House. For many of us in residence at the time, the highlight was a talk by Karen Stevenson (Maryland/DC & Magdalen 1979). In a space so often marked by efforts to impress, posture, upstage, Karen shared her own story with authenticity and vulnerability. She spoke openly about the taboo topic of coming unhinged at Oxford – and about finding a critical community of support amongst Rhodes women.

Over seven years later, many details of her talk have become hazy. But the feeling in the Beit Room that day remains palpable, as does Karen’s crystallization of an experience we, as Scholars, were watching unfold around us, if not encountering ourselves: “unhinging.” Unhinging is decidedly not included in scholarly criteria laid out in Cecil Rhodes’ will. It is decidedly not depicted in portraits adorning the walls of Milner Hall, nor is it catalogued in class letters. And how in the world can anyone coming unhinged “fight the world’s fight”? Yet, for many Scholars, it’s a defining element of the Rhodes experience and, as we have learned since, one of the most critical elements in discovering how we might each fight a good fight in our own way.

What is that unhinging all about? We can only speak with confidence about the stories we know well: our own and those of our close community of Rhodes women, specifically Jeni Whalan (Australia-at-Large & Balliol 2005) and Alex Conliffe (Quebec & Hertford 2004). So that’s our dataset, and we’ll use it to tease out the insights we’ve uncovered through explorations in and with that community – insights that are, necessarily, still emerging and far from definitive.

Let’s be honest, most Rhodes Scholars are really, truly excellent box-tickers. Throughout adolescence and as undergraduates, we diligently, passionately, meet and exceed the expectations of our elders and institutions – wowing teachers of all subjects, setting high water marks for our coaches and instructors, impressing anyone excited by excellence, amassing accolades and awards. Indeed, identifying and excelling at ticking boxes of “success” paves the way to the Rhodes.

We arrive at Oxford, then, having perfected the art of should, and often keenly attuned to the shoulds that can feel bound up with the Scholarship itself: to live up to the potential perceived in us, to pursue a path that befits a Rhodes Scholar, to “fight the world’s fight” in some terribly (and conventionally) impressive way. McKinsey. Google. Yale Law. Prestigious government jobs. Even as Scholars are transitioning to Oxford, they’re already wrestling with the transition beyond the dreaming spires. And deploying should against one another, assessing one another’s notions and choices, can become all too regular a pastime.

As Katharine described in The American Oxonian during our second year: “As we squeeze out of Oxford rich and wonderful experiences, we are haunted by anxiety about what comes afterwards. […] For a group of people who, in many ways, have gotten where they are by seeking to please and have received the constant confirmation that comes along with being a pleaser, the real challenge is being our own evaluators and finding our own sources of satisfaction.” It is no small task to discern a sense of direction and purpose in what Mary Oliver has called our one wild and precious life, and that challenge is only intensified when should looms so large. Too often it blurs our vision, rather than sharpening it, and hems us in, rather than fostering exploration of richer paths.

For our band of Rhodes women, our wrestling with Oxford-and-beyond came in waves – as did the unhinging that accompanied it. For Katharine, it started with transitioning out of an ill-suited MSc and into a deeply enriching DPhil, despite American academic mentors urging that she pursue a “real PhD” in the U.S. Jen, on the other hand, recalls that it started during the DPhil:

I came to Oxford as a lawyer with a passion for human rights and casework that effects tangible change. But after completing the BCL and MPhil, I found my clarity of professional direction muddied. “Of course you should do the DPhil!” people I respect and admire told me with conviction. The world’s top international law academic, my supervisor, assured funding. And the title of “Dr.” was alluring. As a Rhodes Scholar, why wouldn’t I go for the highest academic credential? Of course I should.

But it was a recipe for unhappiness – and then depression. Ultimately, I quit. People told me I shouldn’t “cop out,” I should just buckle down and do it. But after much reflection, I realized the true cop out was staying at Oxford and opting for the path of should. The alternative should of big, prominent law firms was safe and recommended. But I let myself be drawn by the truth of my passion to a small firm where I could do the work I love. And I went from languishing to thriving.

This change of course was hugely victorious for Jen – for her sense of aliveness and her ability to contribute to the world. It opened up a set of professional opportunities she could never have imagined. But while Jen’s work was hitting the front page of the New York Times, hidden behind the headlines was the group of confidants that enabled her to shed a debilitating should.

The four of us are now scattered across three continents and four countries, but somehow continue to gather, once or twice a year. Amidst cocktails and long meals and storytelling, continued exploration of our post-Oxford paths remains a central focus. We have all had our experiences of hitting a dead end of one kind or another – in consulting, in government, in academia – of finding ourselves in roles or ecosystems that we had chosen but ultimately found stunting or even soul crushing. We have all experienced our own unhinging, our confidence deeply knocked and a sense of ourselves as dreamers and doers thrown off kilter.

We have navigated unhinging with one another’s help and support. Our little community provides encouragement to counter the malaise we sometimes find ourselves in and creates space to dream anew. Perhaps most importantly, we remind each other of our authentic selves – the selves our dearest friends see with clarity – and reaffirm the value of being guided by authenticity, rather than the familiar pull of should. This ritual has created a powerful bond between us, and it’s also helped each of us find our way, and continually re-define it.

Katharine, for instance, took a leave of absence from strategy consulting to take an academic book on the road – a seeming detour that helped her realize the necessity of shifting to a professional space where big questions of why take precedence over what and how. Jen also recalls a second critical inflection point, with matters of authenticity at its core:

The four of us are now scattered across three continents and four countries, but somehow continue to gather, once or twice a year. Amidst cocktails and long meals and storytelling, continued exploration of our post-Oxford paths remains a central focus. We have all had our experiences of hitting a dead end of one kind or another – in consulting, in government, in academia – of finding ourselves in roles or ecosystems that we had chosen but ultimately found stunting or even soul crushing. We have all experienced our own unhinging, our confidence deeply knocked and a sense of ourselves as dreamers and doers thrown off kilter.

We have navigated unhinging with one another’s help and support. Our little community provides encouragement to counter the malaise we sometimes find ourselves in and creates space to dream anew. Perhaps most importantly, we remind each other of our authentic selves – the selves our dearest friends see with clarity – and reaffirm the value of being guided by authenticity, rather than the familiar pull of should. This ritual has created a powerful bond between us, and it’s also helped each of us find our way, and continually re-define it.

Katharine, for instance, took a leave of absence from strategy consulting to take an academic book on the road – a seeming detour that helped her realize the necessity of shifting to a professional space where big questions of why take precedence over what and how. Jen also recalls a second critical inflection point, with matters of authenticity at its core:

Just three years after leaving the DPhil behind and beginning legal practice, an unexpected opportunity arose: creating a global program to support emerging human rights lawyers. It would mean another significant rerouting – a very different role at a little-known foundation – and again mentors counseled me to stay put and stay the course. Feeling beaten down by the stress of my work, this should seemed both reasonable and appealingly straightforward.

But Alex, Jeni, and Katharine helped me re-evaluate again amidst new circumstances and to trust my instincts. With their support, I came to see that the law firm job that once excited and sustained me was now limiting, making me deeply unhappy. Beyond titles and conventional trajectories, I gained clarity about the content of this new role and its potential for impact on social justice – both profoundly aligned with who I am and what I believe. Why be one human rights lawyer when you can facilitate so many more?

Jen now spends her days with brave, like-minded young lawyers and their allies, supporting their bold and important work around the world. Much to her surprise, her greatest contribution to “fighting the world’s fight” has not been fighting cases herself, but creating opportunities for so many others to do so.

All four of us are on paths different to those we chose out of Oxford. The journey most definitely continues, but we feel more aligned with true north. We have found our way into roles and ecosystems that allow us to be our more authentic selves, play more to our strengths, and thus make more significant contributions. Getting to this place has had everything to do with the community of reflection and support we share.

For Karen Stevenson, for the four of us, and for so many others, the Rhodes experience sparks a lifelong journey – a journey of navigating away from should and towards authentic choices that allow our true selves to thrive and give. There is no obvious or clear answer on this journey and no path that will resolve the questions. Heeding Rilke’s advice, we can, instead, love the questions themselves, and live them. The Scholarship opens an incredible opportunity to embrace uncertainty, to take risks, to test, tumble, and try again, uncovering insights – often unexpected – along the way.

In this spirit, we reimagine “fighting the world’s fight.” Instead of a dictate – another should – to strive towards, quarrel with, or rebel from, what if we approach this call with a deep sense of curiosity? We might begin to see it as an invitation to explore the intersections where, in Frederick Buechner’s words, our deep gladness meets the world’s deep need – where we can bring the best of ourselves to bear on work that matters. We might begin to see it as a call to support one another in exploration and evolution, rather than a bar by which we can evaluate and should one another.

Remembering that spring afternoon in the Beit Room, we share Karen’s deep appreciation for sustaining relationships among Rhodes women, especially when the road gets rocky. We also know now what we didn’t realize then: there is an unlikely beauty in the unhinging. It injects rich data into our continual process of learning and listening to the lives that want to be, of bringing who we are and what we do, our inner worlds and worldly work, into alignment. It’s amidst unhinging that we may hear the powerful call of must and move beyond the tyranny of should.

All four of us are on paths different to those we chose out of Oxford. The journey most definitely continues, but we feel more aligned with true north. We have found our way into roles and ecosystems that allow us to be our more authentic selves, play more to our strengths, and thus make more significant contributions. Getting to this place has had everything to do with the community of reflection and support we share.

For Karen Stevenson, for the four of us, and for so many others, the Rhodes experience sparks a lifelong journey – a journey of navigating away from should and towards authentic choices that allow our true selves to thrive and give. There is no obvious or clear answer on this journey and no path that will resolve the questions. Heeding Rilke’s advice, we can, instead, love the questions themselves, and live them. The Scholarship opens an incredible opportunity to embrace uncertainty, to take risks, to test, tumble, and try again, uncovering insights – often unexpected – along the way.

In this spirit, we reimagine “fighting the world’s fight.” Instead of a dictate – another should – to strive towards, quarrel with, or rebel from, what if we approach this call with a deep sense of curiosity? We might begin to see it as an invitation to explore the intersections where, in Frederick Buechner’s words, our deep gladness meets the world’s deep need – where we can bring the best of ourselves to bear on work that matters. We might begin to see it as a call to support one another in exploration and evolution, rather than a bar by which we can evaluate and should one another.

Remembering that spring afternoon in the Beit Room, we share Karen’s deep appreciation for sustaining relationships among Rhodes women, especially when the road gets rocky. We also know now what we didn’t realize then: there is an unlikely beauty in the unhinging. It injects rich data into our continual process of learning and listening to the lives that want to be, of bringing who we are and what we do, our inner worlds and worldly work, into alignment. It’s amidst unhinging that we may hear the powerful call of must and move beyond the tyranny of should.

On Purpose

April 8, 2015

Stepping onto a liberal arts campus always feels like coming home. It feels that way for lots of reasons. Because they’re communities where ideas are the connective tissue. Because they’re places where the libraries have friends. But especially because there’s no better ecosystem for a hopeless interdisciplinarian. My advisor at Sewanee, Jerry Smith, would say emphatically: “specialization is for insects.” Perhaps because specialization eludes me like, very much like a zippy winged bug, I wholeheartedly agree.

So I’m going to take this setting and its deeply interdisciplinary purpose as an invitation, maybe even an excuse, to give a wide ranging talk that weaves together multiple, seemingly disparate threads: evangelicals and climate change, civic engagement and dinner parties, a bit of Shakespeare for good measure. It runs the risk of giving you too much insight into the veritable smorgasbord of my educational and professional life, but clemency is what the wine’s for.

The thread that holds these topics together is a question that can be found living comfortably on a leafy green campus like this one, in hearts and minds of all ages, in a high-powered boardroom, or amidst the hustle and bustle of a city: What does it mean to find a sense of purpose? And how can purpose be an animating force for individuals, institutions, communities, and social change? This exploration will give us our conceptual backdrop for conversation over dinner and dialogue about Charleston’s present and future – a weighty, timely topic, given the grievous events of this week.

The dictionary definition of purpose is “the reason for which something is done or created or for which something exists.” That is, the singular raison d’être of a person or a place or an entity. This is the definition we use in our work with companies at BrightHouse. Not what you do or sell, not where you’re going, not how you operate – purpose is the why, why you exist as an organization. We help companies define and live into their reason for being in the world.

“But don’t companies exist to make money?” I am often asked. Sure, companies have to make money to exist, just like we, as human beings, have to eat to stay alive. But as we all know, human life isn’t just about subsistence; it’s about love and laughter, community and connection, struggle and sacrifice, making memories and making a difference. Think of a company you truly admire – not just like or have loyalty to, but really, truly admire. I suspect your admiration isn’t just about shareholder returns; we admire companies that stand for something, that have a compelling role in the world.

Purpose, in this context, is powerful. It gives companies an essential north star that can align and inspire thousands of employees, that can guide the organization even as markets shift and industries transform, that inspires stakeholders, drives societal impact, and ultimately does benefit the bottom-line in significant ways.

It may come as no surprise that the other question I’m often asked is this: “Can you help me find my purpose?” On the one hand, I see each of those questions as a hopeful data-point, suggesting that impact and fulfillment are trumping conventional definitions of success, that meaning is the currency of greatest value, that the human need for wholeness is being heeded, rather than bifurcating “what I do” from “who I am.” But it’s also a question that’s come to trouble me more and more, not just because of the angst that often accompanies it.

What troubles me is the sense of singularity and clarity implicit in the question – and in our public discourse about purpose generally. It suggests that purpose is a thing, a capital “A” Answer – perhaps sitting out there somewhere, waiting for me to find it, if only I had the map; or in here somewhere, if only it would come out to play. It somehow suggests that I’m stuck, waiting for purpose to find and redeem me, so we can be together forever and ever amen. It also suggests that until I have that thing, purpose, I’m simply muddling about in no man’s land, frittering away my life, lost in some kind of unenlightened fog.

This way of thinking about purpose can foster fear and trembling, a sense of paralysis, a wait-and-see approach to life. It can also foster a terrifying level of certainty and resistance to growth and evolution. But if we turn the kaleidoscope just slightly, we can start to see purpose not as an end game but as a way of being.

Stepping onto a liberal arts campus always feels like coming home. It feels that way for lots of reasons. Because they’re communities where ideas are the connective tissue. Because they’re places where the libraries have friends. But especially because there’s no better ecosystem for a hopeless interdisciplinarian. My advisor at Sewanee, Jerry Smith, would say emphatically: “specialization is for insects.” Perhaps because specialization eludes me like, very much like a zippy winged bug, I wholeheartedly agree.

So I’m going to take this setting and its deeply interdisciplinary purpose as an invitation, maybe even an excuse, to give a wide ranging talk that weaves together multiple, seemingly disparate threads: evangelicals and climate change, civic engagement and dinner parties, a bit of Shakespeare for good measure. It runs the risk of giving you too much insight into the veritable smorgasbord of my educational and professional life, but clemency is what the wine’s for.